The War and Emissions Climate Solutions Showcase was co-hosted by the Climate Hub at the University of British Columbia and the Pacific Institute for Climate Solutions on the 19th of November, 2021.

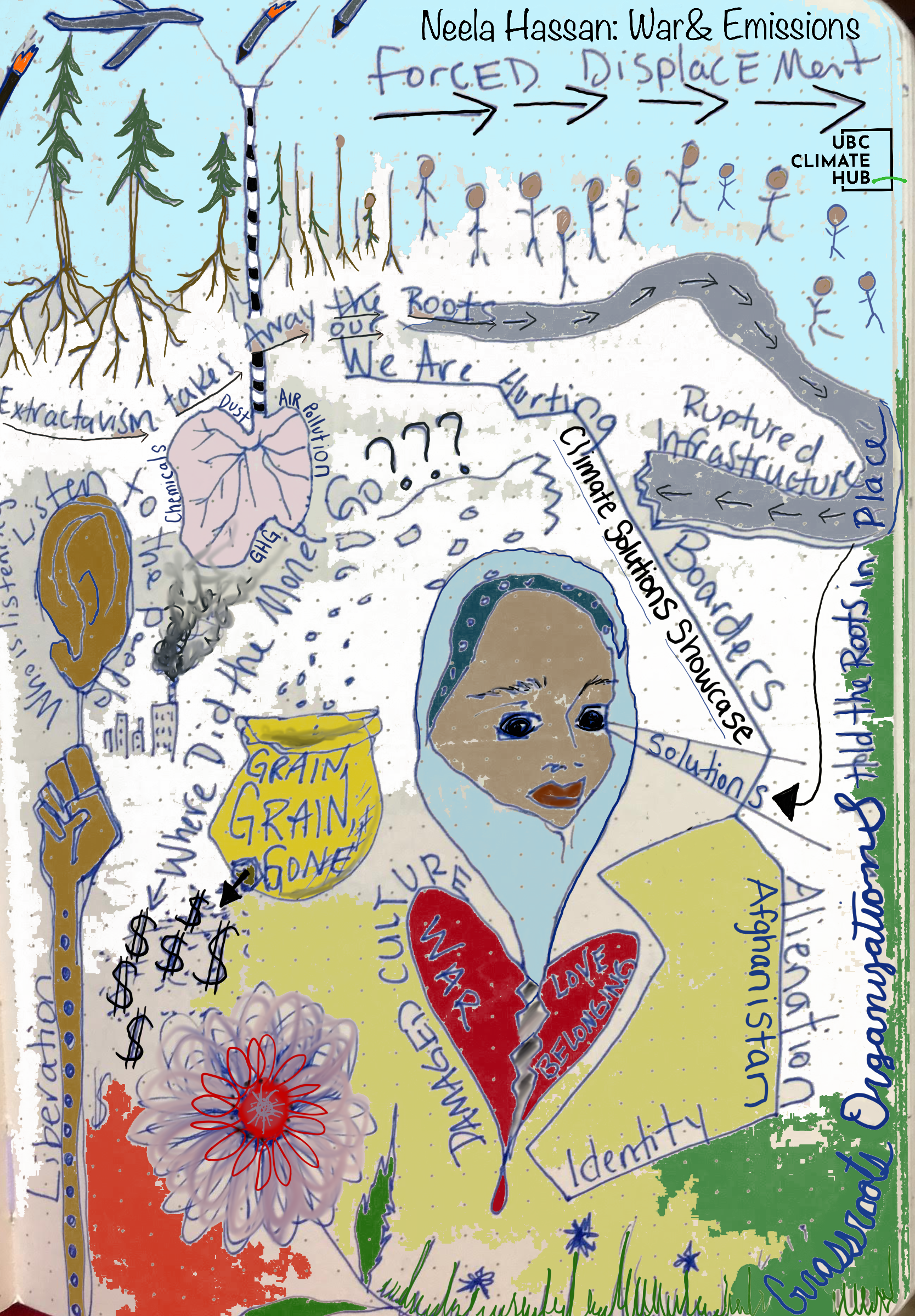

Doctorate of Philosophy student and writer, Dr. Neela Hassan spoke about the political history of Afghanistan and the climate impacts of war. This was the second in a series of Climate solution Showcase events hosted by the UBC Climate Hub.

Author: Charlotte Taylor

We are able to see direct connections between climate change impacts and political unrest in Afghanistan, and many other countries. For this showcase event, Ph.D. student Neela Hassan highlighted the many connections between 20 years of war in Afghanistan and impacts of climate change. The United States’ bombing and the Taliban’s presence, particularly in rural regions, has caused many individuals to feel grief and loss. While bombing created environmental pollution and a significant increase in poor air quality, a lack of social infrastructure also prompted an increase in deforestation.

Colonialism directly strengthens the rapid progression of climate change, which is most disruptive to countries in the Global South. To introduce this concept, Hassan reviewed the historical and political context of war in Afghanistan. Hassan spoke about: the Taliban’s seizing of Afghanistan in 1996, the geopolitical origins of the Taliban, and the recent collapse of the Afghan government (highlighting the 47% increase in civilian casualties since this coup).

The U.S. military is the biggest military producer of carbon emissions in the world. In 2017 alone, the US military emitted more than 25,000 kilotonnes of carbon dioxide. Hassan connected these emissions to the militarization of Afghanistan, which further reinforces the oppression of Afghan women: “They militarized the country but Afghan women were never liberated. Instead, they were more oppressed.”

Afghanistan is the second largest supplier of copper in the world, and they are also home to a wealth of coal, iron, and gold. The regions of Afghanistan with the highest density of precious metals and other natural resources are also largely inaccessible to the Afghan government and media. This is largely due to the presence of the U.S. military in these mineral-rich regions.

Many families living in rural areas burned trees, among other materials, to heat their houses and ward off harsh winter conditions. Unrest in neighbouring countries also led to the illegal exportation of wood out of Afghanistan. The denigration of soil in Afghan forests allowed for flooding, which has displaced more than one million people. Hassan highlights that: “Belonging and identity issues are being created by forced displacement.”

The United Nations now reports that 97% of Afghans are at risk of both hunger and poverty. The cost of these impacts to Afghanistan are astronomical. Attempts by the U.S. to enforce Western notions of women’s liberation onto the highly conservative nation of Afghanistan directly endanger individuals and the possibility of climate justice.

This webinar was concluded with a summation of some important next steps. One solution, highlighted by Hassan, was the importance of communication between negotiators and world leaders. Hassan identified Western intervention and imposition of Western ideals onto Afghanistan as a primary deterrent in effective social and climate justice. Nonetheless, Hassan remains hopeful. She reminded event attendees that “we still have grassroots organizations who are trying to reach people who are in need.”

While some U.S. and Canadian funds were allocated to political aid, individual citizens of Afghanistan rarely benefitted from these resources. This issue can be, in some ways, distilled down to a lack of effective communication. Moving forward, Hassan implores countries in the Global North to listen to activists, politicians, and citizens in Afghanistan in order to facilitate effective climate solutions.

This showcase event helped to host open discussion among UBC community members who are concerned about climate injustice. Taking intermittent pauses during this event allowed attendees to discuss the content of Hassan’s presentation. Additionally, Dr Hassan’s summary of the political history of Afghanistan, and subsequent U.S. intervention, helped attendees discuss issues with the important context of climate change impacts.

If you were unable to attend this event and hope to learn more, recordings of webinar events are available through The UBC Climate Hub’s YouTube page.